In the purest sense, a seed should only produce one outcome; a single pathway to fully formed fruit. The job of the gardener or orchardist is to protect and care for the young life, get out of the way, and give that life every chance of growing into maturity.

But what happens when young growth has some kind of trauma forced upon it?

That’s how I feel about my teenage years, like my maturation veered off course a tad, and my life from then on, for a long time, was anchored to the experience I had as an eleven year old when a school excursion ended in the worst possible way.

Since then I have grown up with an image burned into my brain of my little brother Juddy floating face down in the water, extremely still.

That memory isn’t the one thing that has defined the experience; it’s just the last time I saw him.

Some time later, maybe an hour or so, I was told he had survived the fall. But in the moment I saw him, deep down I knew he was gone. It is etched deeply into my psyche. It is by far the strongest memory of my childhood.

The setting was Kalhatti Falls in Tamil Nadu.

Immediately after he fell, I climbed a few metres down the rapids to the top of the falls to try to get to him. It was all I could do. I carefully placed a foot on a rock, then another, inching my way down a few metres with the water falling underneath and around me until I could see the bottom of the falls. As the pool of water came into my line of sight, I eased my head to the right as far as I could, hands and feet anchored as I straddled the rapids and peered past an outcrop that was blocking my view. That was when I saw Juddy, floating in the water. He was face down with his arms by his side. It was just a second or two. Or was it, who knows? Over thirty years and a lifetime lived and the moment still is, and still isn’t, a blur.

It was also as far down the waterfall as I could climb. There were no more rocks or ledges that I could use. I climbed back up.

Had my mum seen what I did in those few moments there would have been a realisation she may have lost two sons that day.

Kalhatti Falls is beautiful. It is deep in the Nilgiris in the southern part of India. Since then I’ve studied pictures of the falls and can’t get my bearings. The pictures seem more glamourous as they seek to draw the gaze of tourists, showing more water flow than I remember. There were always water shortages in those years. Rations were common. I experienced the falls from the top of the mountain, looking across the valley. Photographers shoot it from the bottom, looking up.

The accident happened on a weekend school excursion. Judson, Kynan and myself had wandered off from the main group. The boys were all in years five and six from the Silverdale dormitory at Hebron School in Ooty. I guess there may have been twenty kids or so aged ten to eleven. We were all playing together and there was some bickering and teasing going on. We decided to leave the main group.

The three of us followed a small stream of water that veered off to the left through trees as we looked out over the valley. When we emerged into a clearing, we were standing at the rear edge of a large, flat, inclining rock that hung 80 feet above the main catchment pool for the falls. We couldn’t see the water smashing into the pool but we could hear it. The main flow of water to our right descended via several metres of rapids and then dropped into a ravine as it became the waterfall.

To our left were dense trees. The view in front was stunning, stretching many miles. I was eleven at the time and in awe of it. Here we were, three young lads, standing on this rock and looking out at the valley and mountains beyond. This was adventure.

We sat down to enjoy the view, several metres from the edge. Was it three or four? It wouldn’t have mattered. Kynan was on my left and Juddy to my right. As Juddy sat I saw the trickle of water and slimey moss beneath him. The wet area of rock extended from some grass behind him to the disappearing edge in front. The instant he touched that rock Juddy started sliding, his back straight as you’d sit up on a water slide with his hands fully stretched either side as he tried to stop himself. He was over the edge in a second.

What was the last thing he said? I have no idea. How I would love to recall those words. I wish I had the insight as an eleven year old to write down my experience, thoughts and emotions during that time. Most of life is about the mundane and the ordinary, maybe what he said reflected that.

He didn’t drown, the autopsy revealed he was killed by a head injury sustained during the fall.

The waterfall is a kind of backdrop to his life. It was fleeting and it was gone, just like the falls. When gazing at falling water, we find moments when the water is in focus for an instant, then gone with a rush as we are left with a shape or a sense of what has been.

That’s how I feel about Juddy. Only a sense of who he was remains.

He lived ten years and he’s been gone three decades and some. Why does loss sit idly by without interfering, sometimes for years at a time, then suddenly become all consuming, as if the entire tragedy has just unfolded?

The shorts he wore that day were polyester, almost plastic. Yellow or blue, maybe both. The fabric may as well have been oiled or greased, such was the slippery combination of the shorts, water and moss. I don’t think he owned any others like it. Who knows whether cotton or denim shorts would have produced the same outcome. Maybe they would have gripped instead.

Kynan went for help. He was gone and it was just me, instinctively moving towards the rapids and waterfall to my right. Apart from a retreat back towards the mountain, the waterfall was the only other exit.

After being defeated by the rapids I was climbing back up when Mr James arrived. He was the supervising staff member on duty that day. He was desperately trying to stay in control, that sense remains clear to me.

Mr James sported a thick dark brown beard that was squared off at the bottom. His walk was strong and he stood straight to the point. He wore short sleeve shirts that were untucked and also squared off. Except for the part in his hair, he was symmetrical. The shirt was a sub-continental cut, a throwback to the British influence in India. Mr James was shades of brown and cream.

In those moments he was controlled in his actions with panic in his eyes. He moved quickly and asked me to rejoin the rest of the group. We waited on the bus for news.

In the weeks after Juddy’s death, the kids at school were amazing. Kids always are as they know how to live in the moment. But for kids, moments quickly transition into new moments. The previous emotion is forgotten. Empathy requires compassion and compassion is selfless. Kids are amazing but most of them aren’t selfless. My experience in the months and years after Juddy’s death was tough. I was grieving but my friends weren’t. There was disconnect and misunderstanding between us and I became uncertain and insecure.

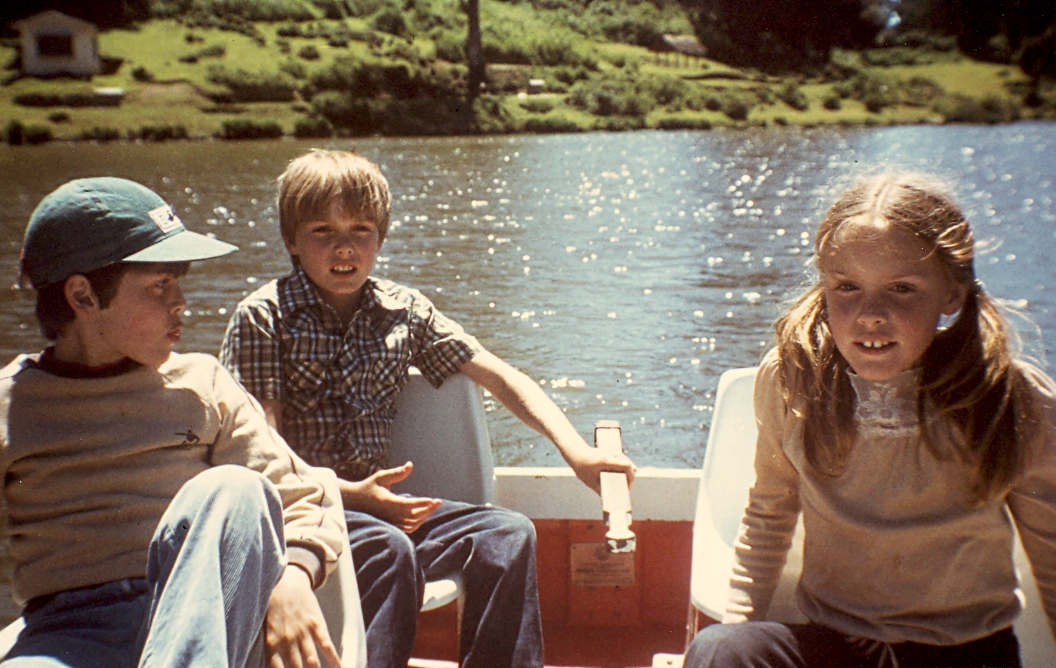

^ Judson in the middle with my sister Vanessa and me

^ This photo was taken of the three of us in Ooty, just weeks before his death

Mr James suddenly appeared at the door of the bus and asked the driver for blankets that were stowed beneath a seat. “Is he going to be okay?” one of the boys asked. Who knows what Mr James really answered. It may have been “yep he’s okay” or “everything will be okay”. Whatever it was, all we heard was the word “okay” and relief swept through the front of the bus accompanied with cheering.

I’ve often thought about his answer. It wasn’t until I settled on these words that it occurred to me that we may have misheard or misinterpreted what Mr James said. My version of the story has always been that Mr James said what a busload of kids needed to hear so he could maintain order and get through the next terrible hours trying to retrieve Juddy’s body. I’ve never held that against him, not for a minute. Here’s a guy who organises a weekend school excursion and he’s suddenly down a student. How do you recover from that?

He left with blankets and the bus was soon en route. We spent the next hour travelling through winding Nilgiris roads, happily singing songs. The first landmark I knew was Shinkows Chinese restaurant before the drive down Church Hill Road and left turn onto the road that would take us towards the Botanical Gardens and the gate to Hebron School.

The bus stopped on the way down the hill and the driver spoke to a person I didn’t recognise. There was something in their conversation that was sombre. I could read the body language of their interaction from the back of the bus. For some, Juddy was alive on that bus ride. But not to me. I was only eleven and my lips were singing. But my heart wasn’t. Fresh in my memory Juddy was face down in the water, not moving. I see it.

When I stepped off the bus, Mrs James was waiting. “He’s going to be okay” I said to her, hoping. She started crying and pulled me into a cuddle. “I’m afraid he’s not, mate”.

My tears were ready to flow, I knew he was gone. I cried, and honestly I have been crying ever since.

I loved that Mrs James used the word mate. I had forgotten that until now. It’s so very Australian. At that moment it contained a familiarity that rang true as my sister Nessy and I were isolated from family. Mrs James was a dorm parent who became an Aussie aunty and a family friend and interim mum.

In the following days Vanessa and I were camped in the James’ apartment and became reacquainted with Lego. Jack James had piles of it including bits I’d never seen before. I got lost in it. It was a numbing, block building experience. Mum and dad were travelling from New Delhi. It’s a long way and the trip isn’t simple. A couple of flights, an overnight stay and a four hour drive up fourteen hairpin bends from Coimbatore via Mettapalayam to Ooty. That period of time seemed to go on for a while in a weird sort of holding pattern. I don’t recall many tears in those days.

Lego, waiting, numbness and more Lego.

Mum and Dad finally arrived. I don’t even remember where I was when I first cuddled them. We had the funeral, but it’s a blur. In fact the memories during those days and weeks are scattered at best.

By far the most powerful memory I have as a kid is the day I lost my brother Juddy as he slid off the rock at Kalhatti Falls.